Two weeks ago, I had a conversation with two friends about English classes. I was talking about how much I loved them, essays come easy to me, the teachers are always great- it really is my favorite subject. My friends, without missing a beat, both vehemently disagreed with me. The word ‘hatred’ and ‘despised’ being used in their explanation of Highschool English classes. I was…. Shocked. they’re both straight A students and pretty eloquent- why did they hate English so much?

One of my friends explained to me, “Every single book I read in English involves rape or SA.”

I paused for a moment. “What? No, that’s not… there’s.. huh.”

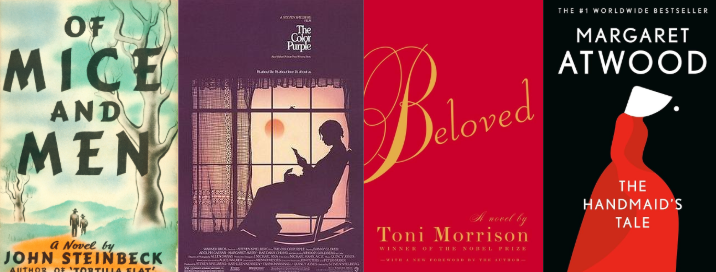

It hit me in a sudden moment. It’s.. More or less true. Highschool level English classes, disturbingly almost always include that topic. These works of classic literature, often assigned reading in high school English classes, reflect the realities of the time in which they were written. They often reflect a time in which women’s safety and autonomy were frequently threatened. “Realistic portrayals of human suffering” is generally the reason, or more accurately, the excuse for having teenagers read about such topics. Why is that okay? Making sure that students understand the topic is important, but doesn’t it get to the point of oversaturation, and more importantly, cruelty. Why does nearly every book you read in English put women in the same roles?

Women’s suffering, past and present, is a reality that literature shouldn’t shy away from. These are real issues that deserve attention. Books that include these topics can create safe spaces for important conversations, and even make a victim feel seen. The problem arises when nearly every book we’re assigned leans on the same storyline: women portrayed as victims. These books are often written by authors who didn’t see value in giving their female characters depth, or even names. Some of these authors, like Charles Dickens for example, were actively domestically abusive and wrote through a patriarchal lens.

Even if a text has nuance, the reality is that it can easily get lost on students. In Of Mice and Men for instance, classroom essays regularly reduce Curley’s wife to ‘evil’ or ‘tempting’ for her actions–teachers frame this as critical thinking. But I believe it is a dangerous oversimplification- especially considering these excuses are used commonly in our social environment. Women ‘deserve’ what happens to them if they’re considered vixens, or cruel by the standards of a patriarchal society. Introducing these topics and requiring students to think about it critically, while encouraging them to see Curley’s wife as evil- during their formative years could negatively impact how they view women in real life.

There is also the issue of balance. When almost every book includes sexual assault against women, but rarely depicts male survivors, the curriculum itself sends the message that sexual violence is something that only happens to women. Given that underreporting among male survivors is already a serious problem, I believe the silence in literature can contribute to stigma. 4 in 5 males who get raped don’t report it. Many survivors believe they’ll be laughed at, or not believed, which can be incredibly terrifying- it could feel impossible to tell your story. With the inclusion of books that depict male survivors, For example- Tonight We Rule the World by Zack Smedley.

Classrooms don’t have to suffer literary merit in order to move away from literature that center sexual assault against women. For instance, Jacqueline Woodson’s book, ‘Brown Girl Dreaming’ is a memoir about identity, family, and growing up black in America. Allowing students to still explore themes of race and misogyny without a central focus on sexual assault. For a classic, Oscar Wilde’s ‘The Picture of Dorian Gray’ is a good option. Classic literary analysis opportunities, with varied female characters and queer themes! Louisa May Alcott’s ‘Little Women’ also keeps with the trend of classics, but includes more layered female characters with struggles and ambitions beyond victimhood or submission.

To another point, we have to ask whether it is ethical to require every student to repeatedly subject themselves to these narratives. In the United states, 683,000 women are raped each year. Millions more experience sexual assault, or witness domestic violence. Many of these survivors- are teenagers. Classmates we walk past in the hallway. Friends who don’t feel safe sharing what they’ve been through. When that’s the reality, should a student’s grade hinge on their ability to reread and analyze a scene that might drag them back to their trauma? What feels like a literary exercise to one student may feel like reliving trauma to another. Is it moral to prioritize the canon over the mental health of students? I don’t think so. Even if we continue to include these books in our curriculum, we should always offer options for required reading that isn’t potentially triggering or sensitive.

Literature can, and should, challenge us. The issue isn’t that these stories exist, it’s that they dominate. Leaving little space for works that center women’s joy, resilience and complexity. If our goal is to educate and empower, then our syllabi should reflect the full spectrum of human experience, not just women suffering.

![With her mom and sister cheering her, senior Maiyah Syed gets recognized on Senior Night for Color Guard, Oct. 10. "It felt pretty good [to be recognized]. I thought it was nice to have all my accomplishments laid out [by the announcer.] [I'm really going to miss] the evening practices and the bonding with the team over everything," Syed said.](https://psouthtreaty.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/emilypiccropped-Gavin-Brady-935x1200.jpg)