Treatment, not judgement

Trying drugs is dumb, but addiction is pathological, not a moral failing.

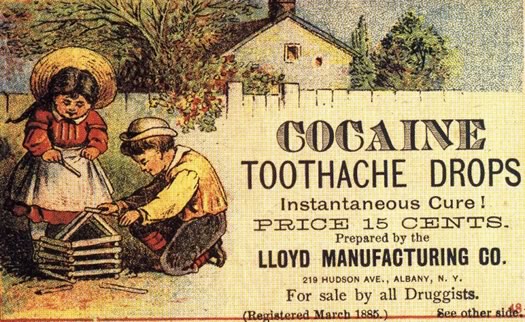

At one point, cocaine was thought of as a treatment for toothaches.

Life is full of things that are harmful to one’s health. Too much fast food can cause high cholesterol, high blood pressure, obesity, Type 2 Diabetes, harm to the immune system, and more. The desire to have a golden tan puts people in tanning beds where they can get skin cancer. Not taking off makeup can damage skin. These are all decisions that many people have made at some point, but people generally do not see these things as morally wrong. However, people who harm their health through substance abuse do not always get the same treatment. In fact, many people see alcoholism and drug addiction as a moral failing, rather than simply another unhealthy choice people make like eating too much McDonald’s. To be clear, I’m not calling for the legalization of dangerous drugs. Rather, I’m saying that trying drugs is a dumb choice but not morally wrong.

Although judgement of people with substance addiction is on the decline, I think it is still prevalent enough to cause great harm. Judging people and looking down on them can affect how we treat individuals suffering from addiction. The negative moral connotation on substance abuse is irrational and did not originate from a place of concern for science or public health and safety. It came from public anxiety about vulnerable groups of people.

Before drugs were associated with Chinese immigrants, black people, and Mexican immigrants, they were normal. Heroin, for example, was once used to treat sore throats, coughs, headaches, diarrhea, stress, and menopause.

But then Chinese immigrants came to work on the railroads and they brought opium-smoking with them. Now all of a sudden opium (and heroin which is derived from it) was evil. People were concerned that Chinese immigrants wanted white women to be addicted to opium. From there on out, the criminalization and negative moral connotation of opium and opium-derived drugs began.

At first, cocaine was used for children’s toothaches and for recreational use. But at some point, white people of the American South in the early 1900s began to project their fear of black people on the substance. Cocaine’s ban followed these anxieties.

Before marijuana was associated with Mexican immigrants, it was used to stop pain and nausea. However, racism and anxiety about job security in the 1930s caused people to point fingers at Mexican immigrants, and soon their drugs. Suddenly, marijuana was seen as a violence-causing drug that could make white women want to have sexual relations with black men.

And the racist overtones continued throughout history. In the 1970s, Richard Nixon declared a war on drugs. But yet again, public health was not the main concern. “We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course, we did,” said John Ehrlichman, Nixon’s domestic policy chief.

So the current system we have to stop substance abuse is not aimed at stopping substance abuse, only getting people into trouble for substance abuse. It has built a culture of shame instead of helping hands.

The system has failed too many people. Alcoholism and drug addiction can eat away at people’s lives. Addiction is nothing but a disease. The chemicals from the drugs and alcohol hack into the brain’s reward system because the chemicals look so similar to chemicals commonly found in the brain. It activates that reward system, making the user feel temporarily good in the same way laying your head on your pillow knowing you’re about to drift off to sleep after two consecutive all-nighters or biting into a sandwich when you’re really hungry feels good. That’s how most people experience the reward system. But with drugs, it is more complicated. Your brain knows that its reward system is being abused, so it tones down the effects of the drugs at the user´s current dosage by dulling the reward system. This means that when the user withdraws, they feel like crap because their reward system is now crap, so they end up seeking the substance in larger quantities or in higher concentrations just to avoid the horrible feelings of withdrawal. For alcoholics, withdrawal can be dangerous without medical assistance because alcohol is a central nervous depressant that the body adapts to. Once the person stops drinking, the central nervous system kicks back in and goes wild, causing shaking, headache, high blood pressure, anxiety, increased heart rate, and in extreme cases, delirium tremens.

The process of addiction is clearly pathological, not immoral. While it is true that everyone should be responsible and not put dangerous substances in their bodies, the irresponsible decision to do so does not deserve emotionally-charged backlash in the case that it evolves into an addiction. People already do harmful things to their own health all the time, and although it can be more harmful, substance abuse should not be treated as morally different.